Did the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status express India’s democratic wish, or did it violate basic democratic canons? The government’s claim is the former, critics say it is the latter. How do we judge?

Democracy has at least four meanings. Democracy, first of all, is a system of electoral power. The BJP received 229 million votes in the recent elections. If all voters were to exercise franchise in Jammu and Kashmir, the erstwhile state would have at best eight million votes, of which the Kashmir Valley had approximately 4.5 million. The BJP has been committed to the abrogation of Article 370, saying it gave undue privileges to India’s only Muslim- majority state. Having received a larger mandate for the directly-elected Lower House of Parliament, and confident that it could get enough votes in the indirectly elected Upper House, it went ahead with its ideological project and removed Article 370 via parliamentary majorities. This is consistent with the first meaning of democracy — namely, electoral majorities as a cornerstone of democratic power.

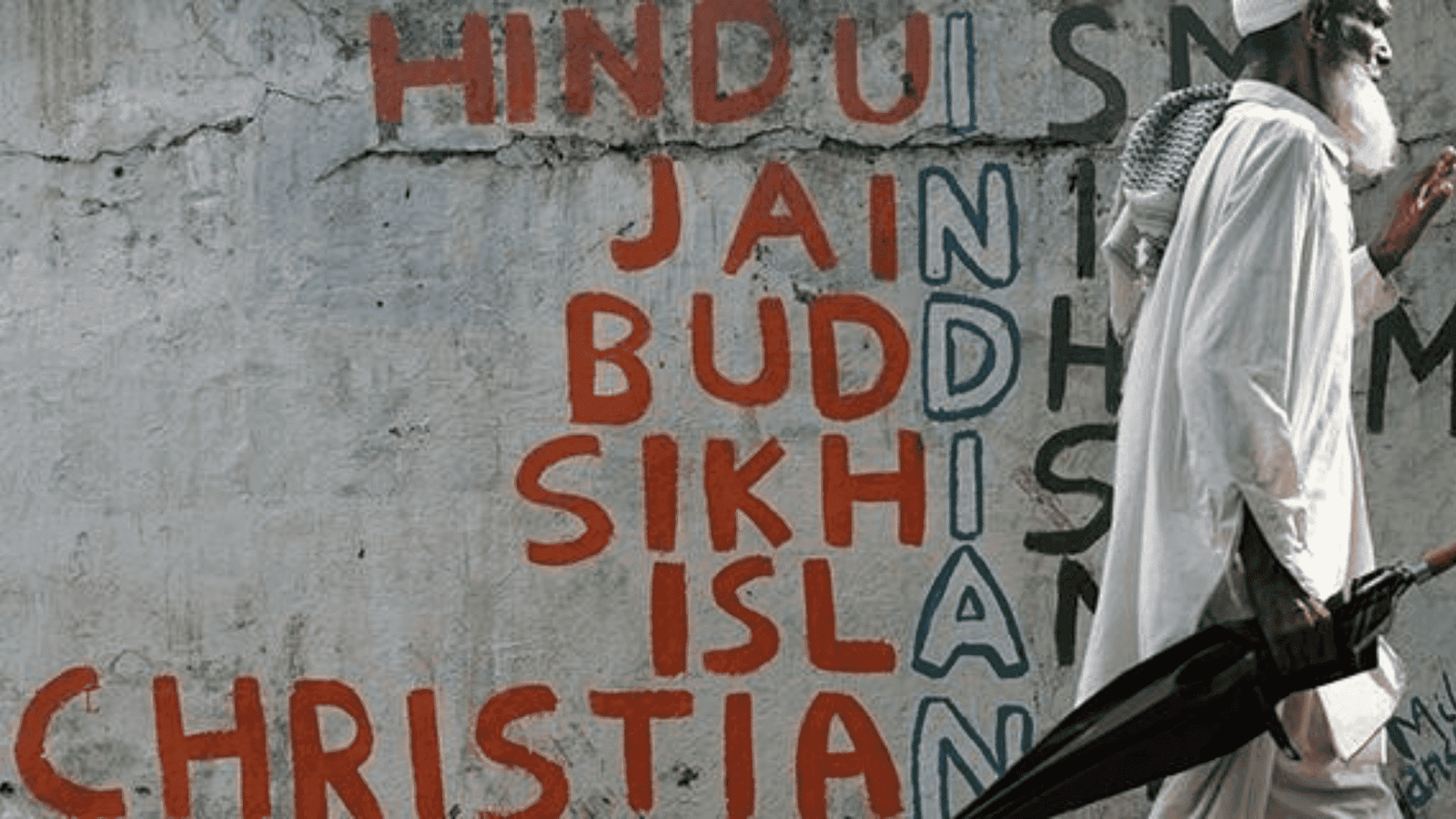

But elections alone do not define democracy. The second idea of democracy is that it is not simply a system of majority rule, but also a system of minority protection. All post-Nazi democracies since 1945 have had this character. The Nazi regime and its theorists, such as Carl Schmitt, had argued that democracy was only about majority wishes and if the German majority wanted Jews to be second-class citizens, the Jewish minority of German lands would have no choice but to submit. Only liberalism, argued Schmitt, protected the Jews, not democracy.

The logical culmination of this view of democracy was the concentration camp, or the incarceration and death of several million Jews because their loyalties to the German nation were considered suspect by those who won power. Unless minority rights constrain the majority-rule principle, democracies can, in principle, lead to concentration camps. That is why post-1945, democracies have tended to be liberal democracies, not simply electoral democracies. Modern democracy first enables majority rule and then also checks and balances it with minority rights.

In and of themselves, 4.5 million votes cannot carry greater democratic weight than 229 million votes. Election winners do get the right to frame policies or enact laws in a democracy, but in post-Nazi democracies, this rule is radically modified when the 229 million voters are primarily of one religion (or race), and the 4.5 million votes are overwhelmingly from a minority religion (or race), as opposed to both being racially, religiously, ethnically so mixed that voters can be identified primarily as individual citizens, not as members of the religiously defined majorities and minorities. The problem is not rule by a majority, but rule by a religiously (ethnically or racially) defined majority.

Nearly 44 % of Hindus voted for the BJP in the recent elections and only eight % of Muslims did. India is about 80 % Hindu, and the Kashmir Valley over 96 % Muslim. The minority- protection principle of democracy means that even with 229 million overwhelmingly Hindu votes, the BJP should not impose its will on seven million Kashmiris. The agreements made to protect minority rights — Articles 370 and 35A — would have to be respected, unless the minority itself agreed to their termination.

It is suggested that Kashmiri Muslims have no right to this reasoning because in the early 1990s, with the insurgency at its peak, they actively engineered the outmigration of Kashmiri Hindus, a minority community in the Valley where Muslims are a majority. This argument is flawed. All it can logically require is (a) identifying and punishing those organisations that forced the outmigration, and (b) insisting on the return of Kashmiri Hindus. By no democratic reasoning does it entitle a government to inflict majoritarian retribution on an entire community — to avenge an earlier majoritarian excess.

The third meaning of democracy is that it is a constitutionally-governed system. All modern democracies, except the British, are constitutionally-based. Elections establish who will rule, but the rulers so elected are also constitutionally bound. Here, there are three key questions.First, can routine legislative action scrap an article of the constitution? Or, was a special legislative procedure, mandated by a constitutional amendment, required? If the latter, the change should also have been proposed as a constitutional amendment, and super majorities in the two Houses of the central legislature pursued ex-ante, not celebrated post-fact. Second, can the governor’s approval, procured in this case, be taken as the state’s consent for change?

Constitutionally, the governor represents Delhi, not the state in question. The governor cannot be called a substitute for the state’s elected political representatives. If the elected state legislature is not in session, a constitutional change pertaining to the state must await the return of elected representatives. Third, we know that Article 3 of India’s Constitution allows the change of state boundaries without the approval of state assemblies, but the Centre, on August 6, did not simply hive off Ladakh from a state, a la Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. It also demoted Jammu and Kashmir. Can India’s Parliament, without a constitutional amendment, turn a state with full federal rights into a Union Territory, which has reduced rights and whose law and order are centrally governed, not by the state? It is analogous to turning Pennsylvania, a state in the American federation, into a Washington DC, which is not a state.

The fourth meaning of democracy is that it is a system of political ethics. In a democracy, those vitally affected by a decision are given a chance to speak, even if they are likely, or destined, to lose. Losers are silenced in authoritarian polities, not in democracies. The Kashmir Valley is vitally affected by this constitutional change, but it was locked down, its leaders arrested, and a curfew imposed. This is similar to what happened on the eve of the Emergency, on June 25, 1975. Indira Gandhi arrested major Opposition leaders before a president-approved order was presented to Parliament and democracy suspended. Since August 5, we have witnessed a Kashmir-level emergency, though clearly not a national emergency.

In short, only in one democratic sense — democracy as a system of electoral power — can the decision to change Kashmir’s status be called potentially legitimate. In all other democratic senses, we have witnessed severely anti-democratic conduct. It was electorally- enabled brute majoritarianism.