In the expansive realm of sociological research, the exploration of social phenomena is intricately shaped by the dichotomy of qualitative and quantitative methods. These methodological approaches serve as the bedrock upon which sociologists build their understanding of human behavior and the complex structures that constitute society. As we delve deeper into the nuanced interplay between these methodologies, it becomes evident that they offer complementary lenses through which researchers can decipher the intricate tapestry of social life.

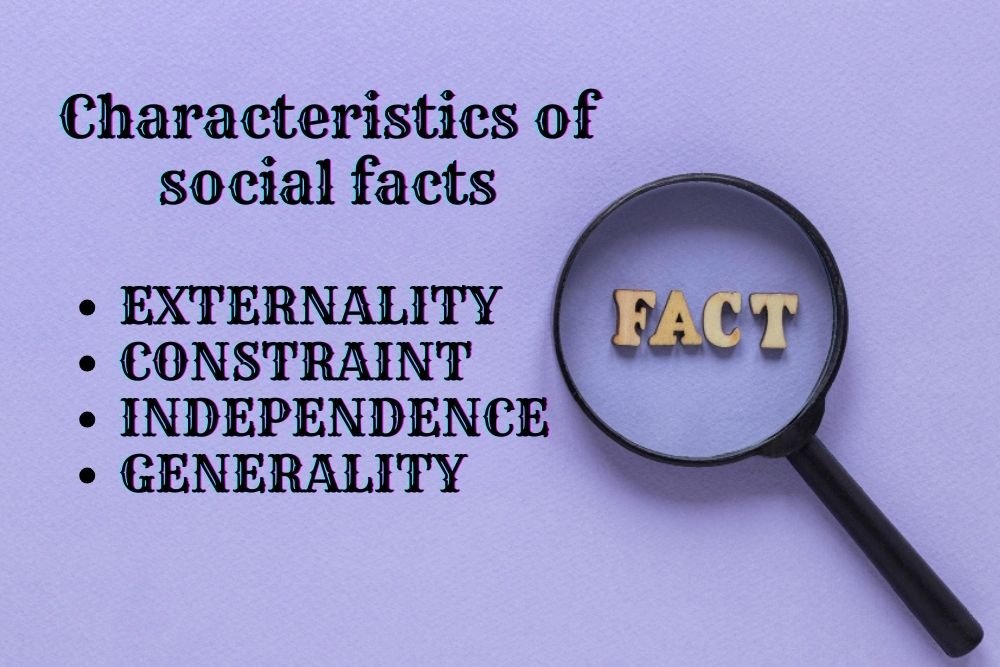

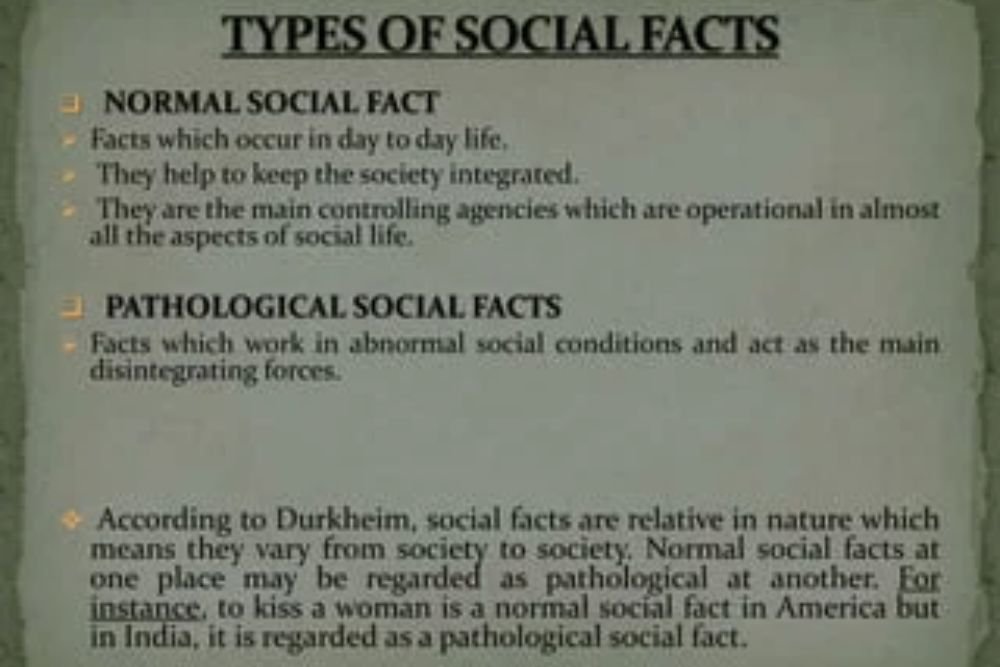

Quantitative methods, firmly rooted in the positivist tradition, embody a systematic and rigorous approach to gathering and analyzing numerical data. This method seeks to quantify social patterns, relationships, and regularities, aligning with the scientific aspirations of early sociologists. The foundational work of Emile Durkheim, notably "The Rules of Sociological Method," underscores the paramount role of statistical data in unveiling social facts and patterns. Durkheim's emphasis on objectivity and the scientific method laid the groundwork for the positivist strand within sociology.

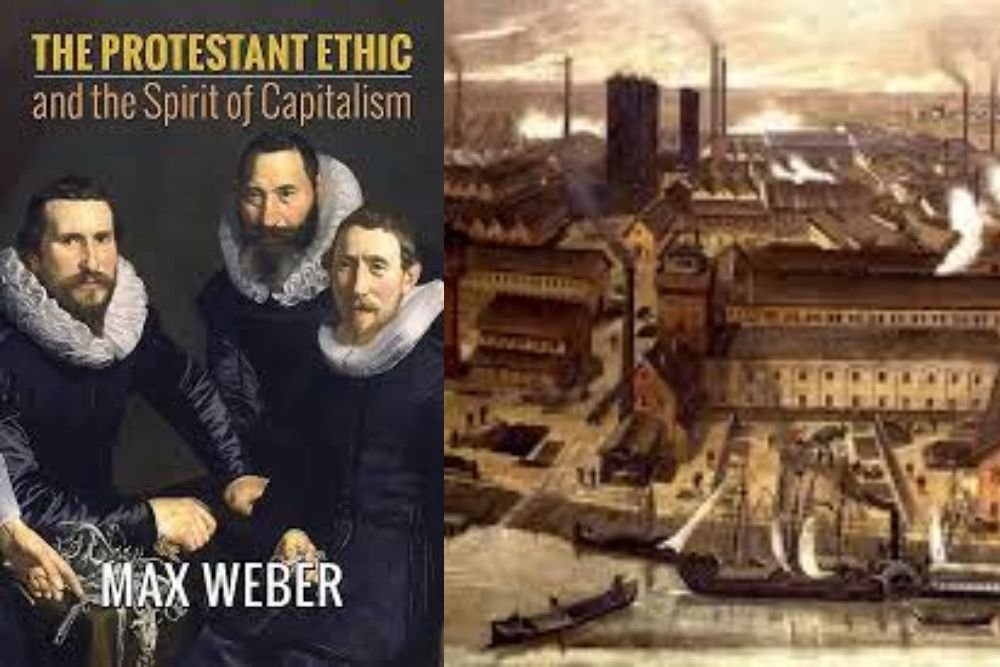

Within the expansive landscape of quantitative research, scholars employ an array of methodologies ranging from surveys to experiments and statistical analyses. The quantitative approach, as exemplified by Max Weber in his exploration of the intricate relationship between Protestantism and the rise of capitalism in "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism," showcases the evolving nature of sociological research and its engagement with empirical evidence.

In stark contrast to the numerical precision of quantitative methods, qualitative methods offer a more nuanced and context-rich exploration of social phenomena. Rooted in interpretive traditions, qualitative research focuses on unraveling the subjective meanings individuals attach to their experiences, thereby revealing the depth and complexity inherent in social life. A towering figure in this qualitative tradition is Erving Goffman, whose seminal work "The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life" delves into the micro-level interactions and symbolic meanings that underpin social interactions.

Prominent within the qualitative tradition is the work of Pierre Bourdieu, whose ethnographic studies, especially "Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste," serve as exemplars of the depth achievable through qualitative methods. Bourdieu's exploration of concepts like cultural capital, habitus, and symbolic violence highlights the significance of capturing the intricate interplay between culture, social class, and individual agency.

The choice between quantitative and qualitative methods is often informed by the researcher's epistemological stance and the nature of the research question at hand. While quantitative methods offer generalizable patterns and statistical rigor, qualitative methods provide in-depth insights into the subjective meanings individuals attach to their experiences.

Anthony Giddens, in his influential work "The Constitution of Society," introduces the concept of "methodological dualism," advocating for a more holistic and integrated sociological methodology. Giddens recognizes the complementarity of both qualitative and quantitative methods, encouraging researchers to embrace a multi-methodological approach to gain a comprehensive understanding of the social world.

Expanding on this dialectic, it is imperative to recognize that the interaction between qualitative and quantitative methods in sociology is not merely a theoretical debate but a dynamic and evolving process. Both approaches contribute uniquely to the sociological toolkit, allowing researchers to uncover the intricate tapestry of human behavior and societal structures. The ongoing dialogue between scholars, guided by the foundational works of Durkheim, Weber, Goffman, Bourdieu, and Giddens, propels the field forward, fostering a more nuanced, holistic, and comprehensive understanding of the complexities inherent in the social world.