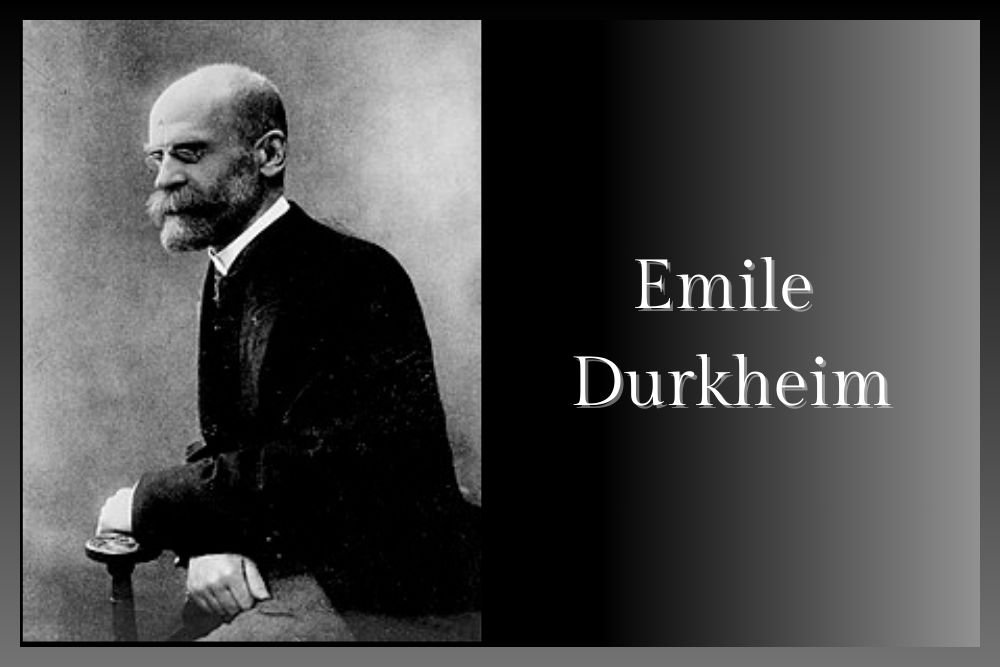

The division of labour, a cornerstone in sociological thought, intricately weaves into the fabric of societal dynamics, offering profound insights into the evolution and intricate workings of human societies. The venerable sociologist Émile Durkheim, in his magnum opus "The Division of Labor in Society," elevates this concept beyond a mere economic phenomenon, portraying it as a powerful societal force shaping the very essence of human interactions and community structures.

Durkheim's classification of social solidarity into two types, namely mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity, adds layers of understanding to the division of labour. Mechanical solidarity characterizes simple, pre-industrial societies, where individuals share similar tasks, fostering a cohesive social fabric grounded in shared values and traditions. In contrast, organic solidarity prevails in complex, industrial societies, where individuals specialize in diverse roles, leading to a higher level of interdependence and a more intricate societal tapestry.

The implications of the division of labour extend far beyond economic structures. In simple societies, individuals engage in comparable tasks, resulting in a close-knit social structure grounded in shared traditions and values. Conversely, complex societies exhibit a sophisticated division of labour, creating a tapestry of specialized roles contributing to societal complexity. Durkheim's insights not only provide a lens to understand societal changes but also emphasize the critical role of the division of labour in shaping social cohesion and community dynamics.

Simple and Complex Society:

The dichotomy between simple and complex societies continues to captivate sociological inquiry, with scholars like Robert Redfield enriching our understanding of their defining characteristics. In his influential work, "The Folk Culture of Yucatan," Redfield unravels the essence of simple societies, predominantly found in rural, traditional settings. Simple societies are marked by a homogenous division of labour, close-knit relationships, and a shared cultural ethos that binds individuals together in a tapestry of communal life.

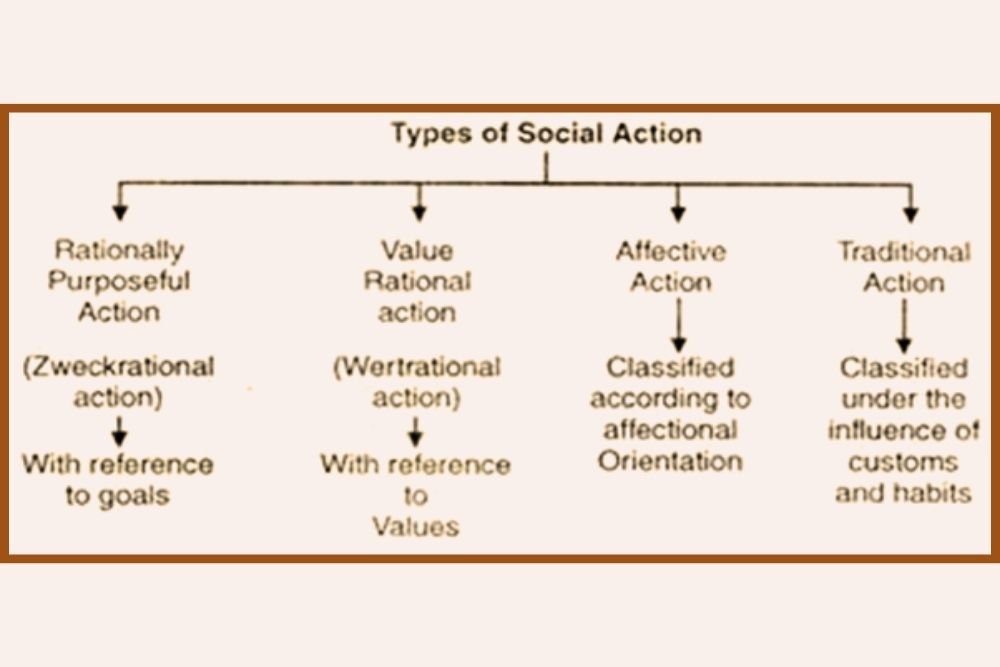

Complex societies, as dissected by thinkers like Max Weber in "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism," stand in stark contrast. Weber elucidates the features of complex societies, marked by urbanization, an advanced division of labour, and a diversified social structure. His emphasis on the influence of Protestant values on capitalism underscores the intricate interplay between religious beliefs, economic systems, and the emergence of complex societal structures that shape the contours of modernity.

Material and Moral Density:

The intertwined concepts of material and moral density deepen our comprehension of social structures, unveiling the intricate dance between spatial arrangements and normative frameworks. Georg Simmel, a luminary in sociological thought, introduces material density in his seminal essay "The Metropolis and Mental Life." Here, Simmel delves into the effects of population density in urban areas on social interactions, unraveling the unique social experience forged by high material density – an experience marked by anonymity and distinctive behavioral patterns.

Moral density, as envisioned by another towering figure, Max Weber, becomes a crucial lens through which we examine shared moral values within a social group. Weber's examination of the Protestant work ethic and its impact on capitalism illustrates how moral density influences economic behavior. The intricate interplay between material and moral density becomes pivotal in comprehending the complex dynamics of societies, where both spatial arrangements and normative frameworks significantly shape individual actions, community structures, and the broader societal ethos.

Anomie:

The concept of anomie, introduced by Émile Durkheim in "Suicide: A Study in Sociology," emerges as a poignant reflection on the state of normlessness or a breakdown of social norms. Durkheim correlates anomie with societal changes, especially the rapid transformations brought about by industrialization and urbanization, leading to a sense of normlessness and elevated suicide rates.

Anomie signifies the disintegration of social bonds and a lack of moral guidance. Scholars like Robert K. Merton further elaborate on Durkheim's concept, examining how anomie contributes to deviant behavior. Merton's seminal work, "Social Structure and Anomie," scrutinizes societal expectations and opportunities for success or strain, unraveling various modes of individual adaptation, ranging from conformity to rebellion.

In conclusion, the exploration of these sociological concepts, elucidated by influential thinkers, becomes a captivating journey into the intricate tapestry of social structures, divisions of labour, societal complexities, and the interplay of material and moral forces shaping human societies. The continued examination and contemplation of these concepts not only enrich our sociological lens but also empower us with a deeper comprehension of the multifaceted nature of societal dynamics across different historical epochs and cultural contexts.